A BookMare

“A book is not a case of words, nor a bag of words, nor a bearer of words.” Ulises Carrion

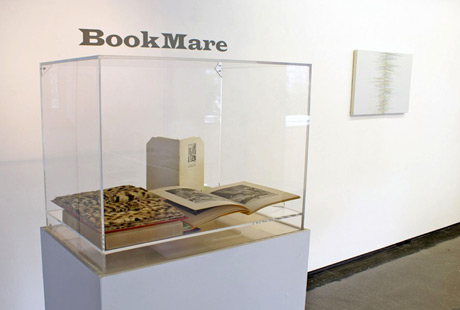

BookMare, curated with Finlay Taylor, at Camberwell Space in July 2012 comprised of an exhibition, performance, talks and discussions exploring how artists have used books as concepts and components in their practice, often causing disquiet. Here, books were not primarily carriers of information – their pages were locked in vitrines, eaten, blown or flashing by at speed. Some books had no text at all, with attention shifting to the artefact itself. This was an uneasy journey through a selection of works to explore territory at the margins of the book.

In the exhibition entrance, setting the scene, were books from the Chelsea College of Art & Design Library chosen by Gustavo Montero-Grandal. Open inside the case lay a double-spread of swooning engraved women from Max Ernst’s Une Semaine de bonte, ou, les sept elements, Capitaux (1934) surreal collages of images appropriated from scientific journals, a study of hysterics Iconographie de la Salpetriere, mail–order catalogues, and natural–history illustrations. Beside this, made fifty years later, was Denise Hawrysio’s iconic fur-paged book Killing (1988) - the leopard skin version. We could see the back cover, by Duchamp, of the New York Surrealist journal VVV (1943) cut in shape of a woman's profile with a piece of chicken-wire inserted across the opening. Standing upright was George Maciunas’ Flux Paper Events (1976) revealing blank pages that had been folded, crushed, stained, torn or stapled. A punched hole went through the whole book and one corner was cut off. Here, the body and the book, became the body of the book, with the perversity of works requiring touch, being locked in a vitrine.

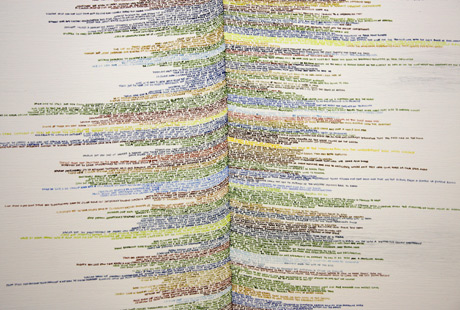

Kate Scrivener’s painting If tomorrow were not an endless journey (2002) which was made originally for Sir John Soane’s angled writing desk at Pitzhanger Manor, hung on the wall. Tiny painted writing formed a book-like image, giving the impression of sensuous page-swell and central gutter. Moving very close, you could read found sentences concerning landscape and weather, painted in greens, blues, yellows and browns. To the left of the ‘gutter’ words read backwards. The sentences, with unjustified frayed edges, seemed to pull in both directions recto and verso. With the gutter giving the appearance of sucking text in - quantities of information moving into itself. Our reading processes being disturbed and questioned.

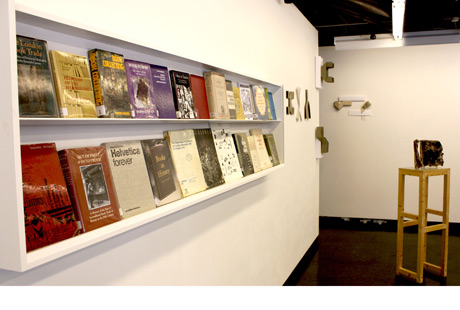

Turning, we saw Mark Harris’ Continuous Defence (2012) an arch constructed especially for BookMare from scores of triangles cut from old book covers, glued and overlaid. The arch, a structural innovation that enabled weight-bearing architecture to evolve ‘supporting civilization’ here serves as a useful metaphor for the book, supporting the retention and distribution of knowledge. The cut covers were from books discarded by Kingston University Library – their innards previously utilized by students. (Harris was keen that no parts of the book ‘carcass’ were wasted). Past the ragged arch hole a long shelf-unit held Arnaud Desjardin’s Works from Stack 655 (Camberwell College of Arts Library 2012). These were battered, functioning books to handle and read, ‘work horses of the BookMare’ Arnaud called them. Twenty-four books culled from stack 655 in the library that cumulatively presented a snapshot of the College’s long-standing engagement with the book as well as a wider culture of book history. They encompassed production, binding, design, archiving, conservation - becoming what Clive Phillpot named a ‘three-dimensional bibliography.’

(See appendix for book list)

The Gefn Press, Cunning Chapters (2007) curated with Katharine Meynell, spilled from another wall. Here, thirteen artists considered the ephemeral and materially unstable in chapters linked by ideological concerns of ‘well-madeness’ loss and conservation in the production of artwork. The chapters used various papers and technologies including newsprint, Offenbach bible paper, buried and excavated sheets encrusted with dirt, delicate insect-eaten cartridge, fold-outs unmanageable and unruly in different sized pages, all united by a Coptic binding. These chapters – giving evidence of wear and tear, use and time - were placed on an angled shelf for readers to handle.

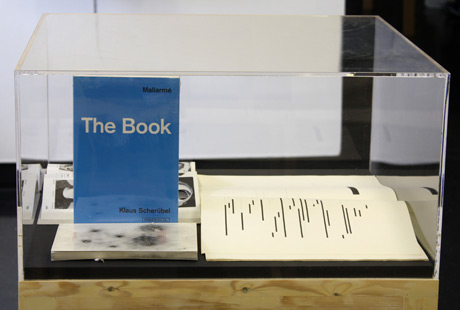

A second case of works from the Chelsea College Special Collection presented processes of deletion and loss. Marcel Broodthaer’s Un Coup de des jamais n’abolira le hazard (1969), an iconic transcription of Mallarme’s seminal non-linear poem fused into lines of black bars across white pages. Here again, our reading processes interrupted. Beside it, propped upright, Klaus Scherubel’s Mallarme: the book (2004) a solid book-block of styrofoam representing Mallarme’s unrealised project entitled Le Livre (The Book), which he envisaged as the sum of all books. Kendell Geers’ Point Blank (2003) where seven bullets were shot into a blank book. The cover with holes and the residue of gunpowder, is a visual record of this event, shocking yet aesthetically restrained. Denise Hawrysio’s book Cut-outs (1993) with the faces from an actors casting book removed - leaving layers of face-shapes visible down through the pages. A lacy ghost-filled directory with its original function lost. Through reworking and altering notions of authorship are called into question.

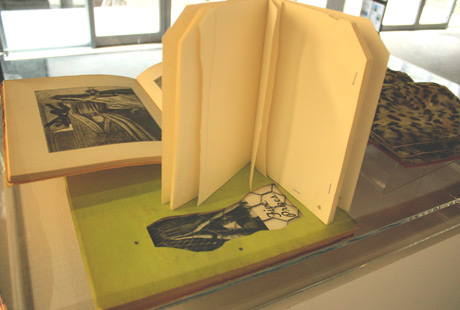

In the next vitrine Damien Hirst’s extravagant pop-up book I Want To Spend The Rest Of My Life Everywhere With Everyone, One To One, Always, Forever, Now (1997) was appropriately inaccessible alongside Helen Chadwick’s elegantly produced et in arcadia (1995) presenting a large cockroach etched onto a heavy marble tablet, inked but not printed and housed in a leather bound box.

Along the walls tied to nails, were Les Bicknell’s smocking is evil (2012) folded and sewn book works. Beige, white, flecked grey, tense with folds, they evoked the hidden. Their forms referenced complex glyphs or very large bats, with dark threads dangling. Huddled in corners and up the walls in little groupings - one positioned high by a door-opening mechanism, perhaps not noticed.

Bicknell also designed the BookMare publication as a single sheet, folded and slit to become a complex structure. The uncanny physical bookness of two becoming three dimensions - surface and depth at the same time.

The opening of BookMare featured Pupa Press, landscapist (an opening event) (2009) a pop-up occurrence reminiscent of Bob Cobbing’s sudden performances at London book fairs. Eight performers mingled within the private view. Without warning each unfolded a book to arm-span, paused, and turned. The body-scale books quivered open for a moment like butterflies, then at a signal, were refolded into their manila covers. The gridded folds referenced maps and integrated into the briefly glimpsed landscape imagery of tarns, sheds, hillsides, ponds, and clouds. Just this moment of revealing - as no evidence of the event was retained in the exhibition.

At the back of Camberwell Space two flipbooks sat on a small shelf James Keith’s Snow and Dust (2011). When activated/flipped, multi-coloured dust flecks or snow flakes gave the illusion of hovering above each book, conjuring the dust of old books or the freshness of snowfall. A sense of daydreaming or private reverie - to watch snow or dust in the air. On the wall, George Eksts’ Age of Mammals (2011) presented a book left out in the landscape in a looped video of blowing pages. Wall-hung to picture height, the framed flat-screen monitor evoked 17th Century vanitas still-life paintings. This work was produced digitally to have a filmic feel, sharp focus with a shallow depth of field. It was possible to fleetingly read phrases such as: ‘there comes a break in the record of Rocks’ ‘The cold has killed them’ ‘these traces are not bones.’ The book pages continually flopped back to the same chapter, stuck in the age of mammals.

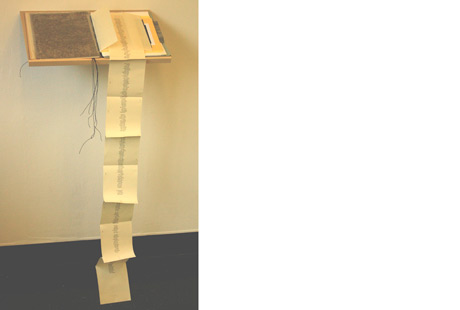

Attached to a plinth was Finlay Taylor’s East Dulwich Dictionary (2007)

a dictionary left out on the ground for months to be eaten by slugs, worms, snails, woodlice. Leaves, dirt twigs and faeces now embedded into its surface. The dictionary, a material object that names the world, in tension with the (named) animals that consumed it as food. Tunnelled with eating trails, a few tiny text fragments remained ‘tempt/to fail to/up a resist/expos’ like bits of poetry gleaned from an archive, uneaten depths of the Dictionary. This work lightly referencing John Latham’s 1966 ‘Still & Chew’ book-consuming event.

Beyond the Dictionary and projected into an alcove was John Latham’s Encyclopedia Britannica (1971). A film of the entire Encyclopedia laboriously created by hand turning and filming each page. It was a filmmaking event/performance with all the slippages and over-exposures included, quickly jumping from page to page, sometimes the light hurting your eyes or the speed and flicker making you feel seasick. An unknowable mass of information punctuated with sudden indecipherable illustrations. The Flat Time House curator Claire Louise Staunton mentioned Latham’s discussion of it as a ‘non-moving film’ with the stop-frame images becoming a film through sequence and time. She also spoke of Latham seeing the book as an ‘everyday object’ and as an event, shifting the literary into physical form (a thing). The façade of Flat Time house is penetrated by a giant book construction pushed midway through the window glass (screen) to be part inside, part outside. Taking the Encyclopedia Britannica as evidence of achievement and knowledge, and with the loss of the readable through speed, Latham’s 1971 film re-materialises the book into movement, time and light – prefiguring Google’s mass book-scanning and the Internet itself.

Susan Johanknecht

This text was originally commissioned by the Tate and Chelsea College of Art Research Network, ‘Transforming Artist Books’ coordinated by Beth Williamson and Eileen Hogan